A1C can sometimes feel like a grade to people with diabetes, which leads to feelings of shame and judgment, instead of empowerment in their care. Time in range can help bring this empowerment back to people with diabetes.

Over the past 25 years, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices have come a long way, offering a variety of options and incredible insights and information for people with diabetes. Currently, more than 9 million people worldwide are using CGMs to manage their diabetes. Numerous clinical trials have demonstrated that regular use of CGM devices can lead to reductions in hemoglobin A1c (A1C) levels and/or episodes of hypoglycemia. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that CGM-based metrics, like Time in Range (TIR), correlate with reduced risk of developing or progressing diabetes-related complications.

While A1C has been the standard for many years, it fails to capture variability in glucose levels and it can delay feedback on changes to diabetes management and treatment. A significant drawback of relying solely on A1C is its potential to negatively affect psychosocial well-being. Much like academic grades summarize performance throughout the grading period/semester, A1C provides a numerical summary of a person’s glucose management over time.

For many individuals, A1C acts as a “pass/fail” grade, which may perpetuate feelings of guilt, blame, or shame. For some individuals, internalizing these feelings, known as self-stigmatization, can lead to a negative self-image and/or a negative relationship with their diabetes. Research shows that diabetes stigma is associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and reduced general emotional well-being. People who experience diabetes stigma report lower quality of life or life satisfaction, self-esteem, and resilience, and more difficulties with interpersonal relationships, less social support, and loneliness. Despite A1C’s usefulness in assessing long-term glucose management, its impact on psychosocial well-being underscores the necessity for a more comprehensive assessment of diabetes management.

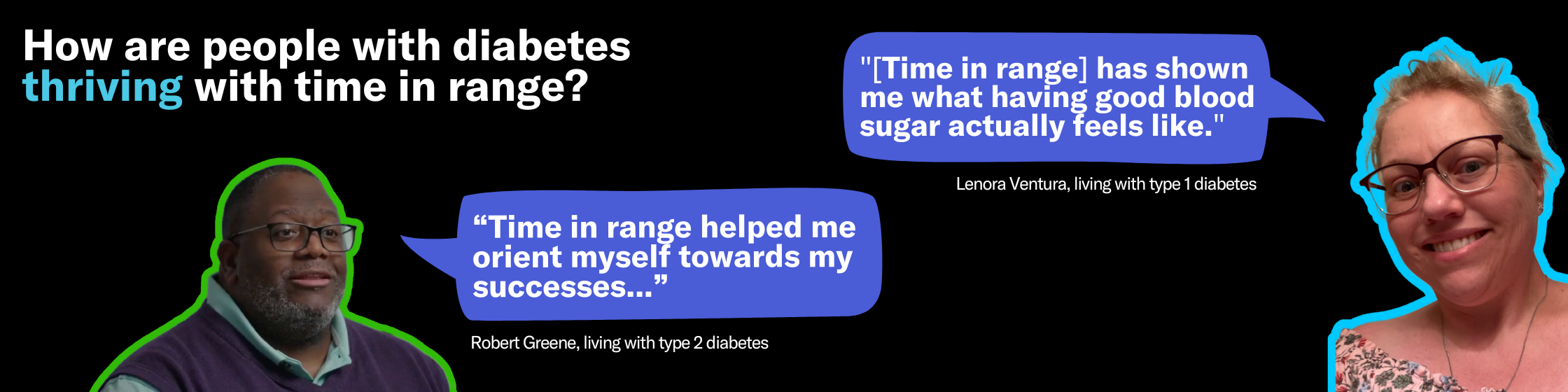

Time in range shifts the focus from the rigid “pass/fail” framework of A1C to continuous improvement with pattern identification. TIR provides minute-to-minute insights into glucose levels throughout the day and offers immediate feedback on adjustments to diet, exercise, and medications. It can be personalized to meet individual needs which can enhance a person’s self-efficacy to manage their condition.

Most importantly, TIR encourages individuals to view each day as a fresh start for self-management. This shift has the potential to transform diabetes management from a judgmental experience to an empowering one. By emphasizing continuous improvement over a singular, long-term outcome, TIR can encourage people to embrace small incremental improvements. By focusing on small steps, people can make adjustments along the way, learning from each experience. This approach fosters problem-solving skills and builds resilience for managing future challenges more effectively.

Healthcare professionals should collaborate with people with diabetes to set realistic, individualized TIR goals that consider their unique values, preferences, and circumstances. This approach ensures that measures like TIR are used constructively to inform and improve care, enhance self-esteem and psychosocial well-being, rather than act as strict benchmarks that must be met. Incorporating TIR as a complementary metric with A1C can help alleviate the pressure and worry associated with “passing” or “failing” this diabetes “test” and reduce the psychosocial burden associated with A1C.

Realistic, individualized time in range goals are empowering and exciting—they take the power away from A1C and empower people with diabetes to take action to live the healthiest, happiest lives possible.

References

Beck RW, Riddlesworth TD, Ruedy K, et al.; DIAMOND Study Group. Continuous glucose monitoring versus usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving multiple daily insulin injections: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:365–374

Browne JL, Ventura AD, Mosely K, Speight J. Measuring the stigma surrounding type 2 diabetes: development and validation of the type 2 Diabetes Stigma Assessment Scale (DSAS-2). Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 2141–48.

Browne JL, Ventura AD, Mosely K, Speight J. Measuring type 1 diabetes stigma: development and validation of the type 1 Diabetes Stigma Assessment Scale (DSAS‐1). Diabet Med 2017; 34: 1773–82.

Fisher L, Polonsky WH, Perez-Nieves M, Desai U, Strycker L, Hessler D. A new perspective on diabetes distress using the type 2 diabetes distress assessment system (T2-DDAS): prevalence and change over time. J Diabetes Complications 2022; 36: 108256.

Garg SK. Past, Present, and Future of Continuous Glucose Monitors. Diabetes Technol Ther 2023;25(S3):S1–S4.

Grace T, Salyer J. Use of real-time continuous glucose monitoring improves glycemic control and other clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients treated with less intensive therapy. Diabetes Technol Ther 2022;24:26–31

Gredig D, Bartelsen-Raemy A. Diabetes-related stigma affects the quality of life of people living with diabetes mellitus in Switzerland: implications for healthcare providers. Health Soc Care Community 2017; 25: 1620–33.

Gubitosi-Klug RA, Braffett BH, Bebu I, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in adults with type 1 diabetes with 35 years duration from the DCCT/EDIC study. Diabetes Care 2022;45:659–665.

Holmes-Truscott E, Ventura AD, Thuraisingam S, Pouwer F, Speight J. Psychosocial moderators of the impact of diabetes stigma: results from the second Diabetes MILES – Australia (MILES-2) study. Diabetes Care 2020; 43: 2651–59.

Housni A, Katz A, Kichler JC, Nakhla M, Brazeau A-S. Portrayal of perceived stigma across ages in type 1 diabetes—a BETTER registry analysis. Diabetes 2023; 72 (suppl 1): 624.

Laffel LM, Kanapka LG, Beck RW, et al.; CDE10. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;323:2388–2396.

Liu NF, Brown AS, Folias AE, et al. Stigma in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Clin Diabetes 2017; 35: 27–34.

Martens T, Beck RW, Bailey R, et al.; MOBILE Study Group. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;325:2262–2272

Nefs G, Bazelmans E, Marsman D, Snellen N, Tack CJ, de Galan BE. RT-CGM in adults with type 1 diabetes improves both glycaemic and patient-reported outcomes, but independent of each other. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019 Dec:158:107910. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107910. PMID: 31678626

Ortiz-Domenech S, Cumba-Avilés E. Diabetes-related stigma among adolescents: emotional self-efficacy, aggressiveness, selfcare, and barriers to treatment compliance. Salud Conducta Humana 2021; 8: 82–96.

Pedrero V, Manzi J, Alonso LM. A cross-sectional analysis of the stigma surrounding type 2 diabetes in Colombia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 12657.

Tamborlane WV, Beck RW, Bode BW, et al.; Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Continuous glucose monitoring and intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1464–1476

Zhang YB, Yang Z, Zhang HJ, Xu CQ, Liu T. The role of resilience in diabetes stigma among young and middle-aged patients with type 2 diabetes. Nurs Open 2023; 10: 1776–84.