Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) allow those you care for to monitor meaningful diabetes management metrics like time in range (TIR), a reliable indicator of risk for diabetes-related complications.

With this data at your fingertips, you can see the full picture of someone’s glucose, identify patterns, and suggest strategic adjustments that help people with diabetes in your care spend more time in range.

Want to incorporate CGM and time in range in your clinical practice? Check out this toolkit to help you get started!

In this article we’ll share a few strategies you can discuss with someone living with diabetes, to troubleshoot towards their TIR goals:

- Put CGM settings to work—a quick change in settings or alarms can make it easier to stay in range.

- Avoid overwhelm—use CGM data to focus on one time of day that is trickiest, so that diabetes doesn’t steal the spotlight all day long.

- Be a pattern detective—talk through factors in the person’s life and diabetes management that coincide with that time of day (you’d be surprised what might be at play!)

- Focus on one thing at a time—the goal is to support a realistic, sustainable shift in health behavior, not shame or discourage with a laundry list of problems.

- Celebrate each win—celebrate every bit of success. Even tiny changes can make a big difference in how someone feels now and down the road.

- Stand in solidarity—recognize that none of this is simple! Validating the difficulty of managing diabetes 24/7 and connecting someone to other resources or communities of people with diabetes can help prevent burnout

Let’s dive into each of these a bit more:

Put CGM settings to work

Review alert settings to facilitate early intervention. Consider setting alarm thresholds inside the target glucose range (e.g., High Alarm at 160 mg/dL; Low Alarm at 80 mg/dL) to prompt the person to address glucose trends before it becomes a high or low.

Keep in mind, this will likely result in more frequent alarms. If the person you’re caring for begins to indicate alarm fatigue (which can negatively impact management and contribute to diabetes distress), consider taking a break and offer this strategy at a later time.

Avoid overwhelm

Shifts in diabetes management, like most health behaviors, can be very difficult. Using CGM data to identify specific timeframes they’re often out of range can help you set focused, attainable goals together.

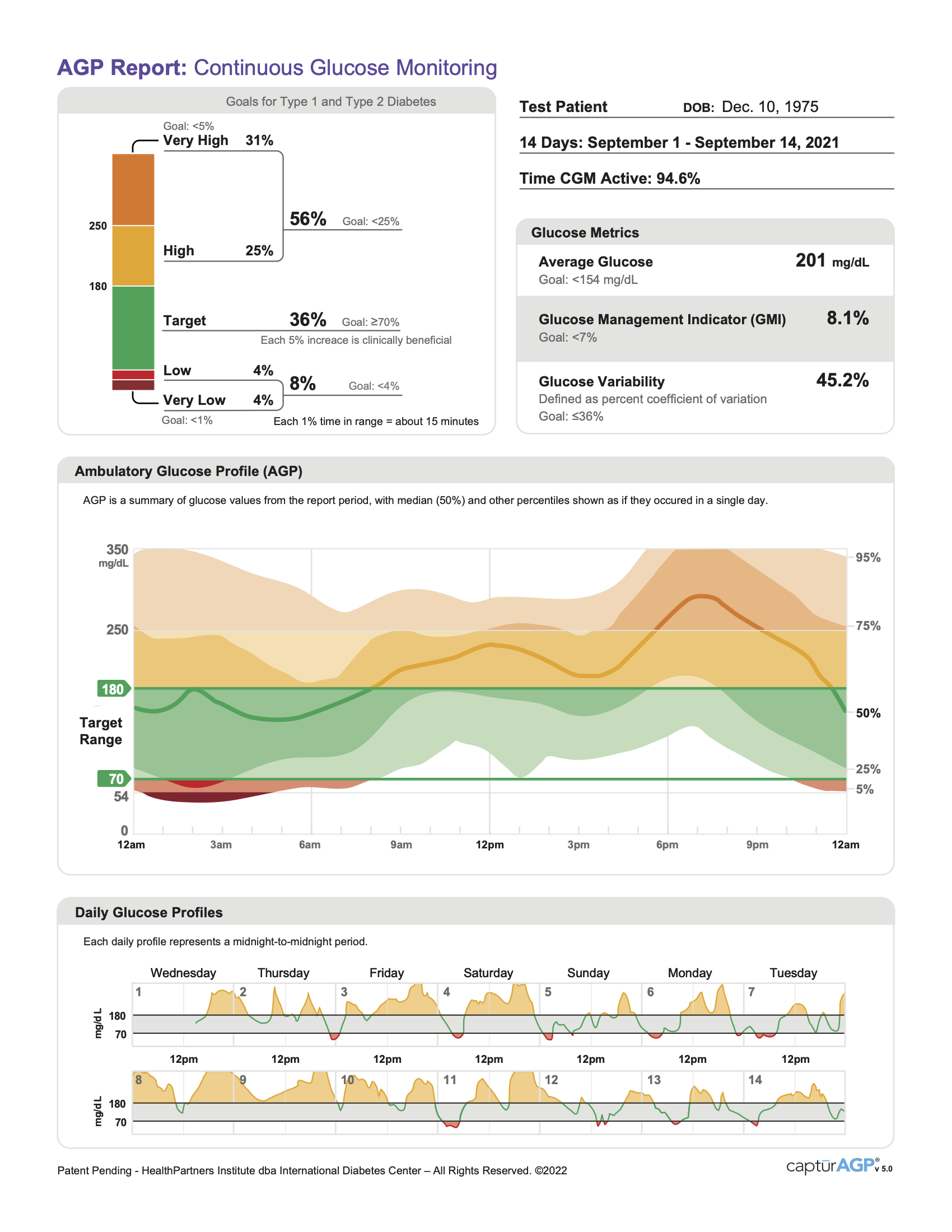

Most CGM data portals generate an AGP report. These reports are standardized, so once you get used to them, you’ll be able to quickly find the information you need from person to person (even if they’re using different devices). The AGP report can help answer three important questions:

What time in range goals are/aren’t being met? Identify one goal to focus on – If time above range goal is just slightly above target, but time below range goal is much higher than the target (4%), focus there first!

What time in range goals are/aren’t being met? Identify one goal to focus on – If time above range goal is just slightly above target, but time below range goal is much higher than the target (4%), focus there first!- What time of day is the person usually out of range? The graph in the middle of the AGP reportcan help you easily spot parts of the day when your patient tends to be above/below their target.

- How are things different day-to-day? At the bottom of the report, you can compare blood sugar trends from thelast 14 days individually. What days were they in range the most? Are weekdays different from weekends?

While pulling up this data may take a few precious minutes of an appointment, it can facilitate a validating conversation with the person in your care, and better inform your shared decision-making about any changes that may need to be made.

CGM data can be a game-changer outside of appointments, too—encourage those you care for to engage with their data outside appointments, too. Small steps like opening the weekly email report that many CGMs send to users can help someone build the habit of keeping an eye on their trends and reinforce the management shifts you discussed. Research shows that opening these weekly summaries and learning to interpret the AGP report can help people with diabetes increase time in range, and make them more confident in their self-management.

Be pattern detectives

Once you’ve identified a time to focus on, have a conversation with the person about what life looked like during the time period where the pattern occurred. Things to consider include:

- Medication: Does the focus area coincide with times they forgot medication? If bolus insulin is part of the treatment regimen, consider discussing the timing of the dose or the method of carb estimation.

- Food: What was for dinner? There are many complicated factors at play around meals—validating this and being careful not to mix any shame into the conversation will support an open and honest conversation about what may have gone awry. Many people with diabetes may benefit from additional support with a nutritionist or educator, or shared resources about how different types of carbs (plus any accompanying protein, fat, or fiber) impact glucose, as these factors can easily disrupt otherwise successful management strategies.

- Exercise: Some forms of exercise can spike blood sugar mid-activity, while others reduce blood sugar long after a workout is complete. Discussing whether the focus period is before or after their gym time, and if patterns look different on days with different types of exercise can help them begin to anticipate and address patterns accordingly.

- Non-diabetes medications, alcohol, drugs, or caffeine can all affect blood sugar, sometimes in unpredictable ways. Were any of these in the mix during the focus period?

- Hormones: If the person menstruates, what phase of the cycle were they in? Encourage them to begin to note whether glucose patterns during the focus period look different during a week when they’re on their period versus during the follicular phase. If discussing patterns over a larger period of time, consider whether longer-term hormonal shifts related to puberty or menopause could be at play, too.

- How are you feeling? It can be helpful to discuss that even running low on sleep, experiencing extra stress at work, or feeling under the weather can all affect a person’s glucose levels(usually causing it to trend higher). While it may seem like getting in the weeds, talking through possible factors can help demystify frustrating patterns for a person with diabetes, and avoid defeating feelings of shame from not doing it ‘right.’

If the conversation isn’t yielding a clear culprit (or more likely, you’re running out of time), encourage the person in your care to read up on these 42 factors that can affect blood sugar — taking some time to familiarize themselves can help you both identify and troubleshoot patterns moving forward.

You may also suggest ways to collect more information alongside glucose data, to guide your future discussions. Many CGM apps allow users to log food, exercise, and other notes. A few extra seconds to log these things as they happen can really help with deciphering your patterns later on.

Focus on one thing at a time!

Avoid suggesting a laundry list of changes. Changing five things at once will make it difficult to distinguish what helped or didn’t, and will likely make it difficult to sustain changes long-term.

Think about small changes you could discuss based on the factors observed that coincide with the focus period. Here are a few examples of things we’ve tried:

- Spikes after a mid-afternoon snack→ Pair carbs with fat, fiber, or protein

- Lows as they arrive at work → bolus a little less for breakfast, knowing the walking during their commute will bring things down

- Stubborn highs after breakfast → Pre-bolus earlier, while getting ready for school before eating

- Highs around bedtime → Try taking a walk after dinner to increase insulin sensitivity

No matter what change you land on together, encourage the person to be patient and observant as they learn how these small changes can affect their time in range.

Celebrate each win

At the next visit, reflect on any small increases in time in range or sustained habits and celebrate that success! Even experiments that don’t immediately benefit glucose levels can help you work together to find one that does, and just a 5% increase in time in range is considered to be clinically meaningful.

Stand in solidarity

Living with diabetes is a complicated job with no days off. Just recognizing the effort this takes can help a person with diabetes know you’re on their team, even when visit time is limited. Sharing resources or communities for people with diabetes in your area can make a big difference between visits.