Time in range (TIR) has been found to be associated with diabetes-related microvascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy). Emerging evidence documenting its association with complications makes time in range a practice-changing metric to be used in clinical care—increase in time in range is shown to potentially reduce the risk of diabetes-related complications.

What does the research say? Let’s go back in history…

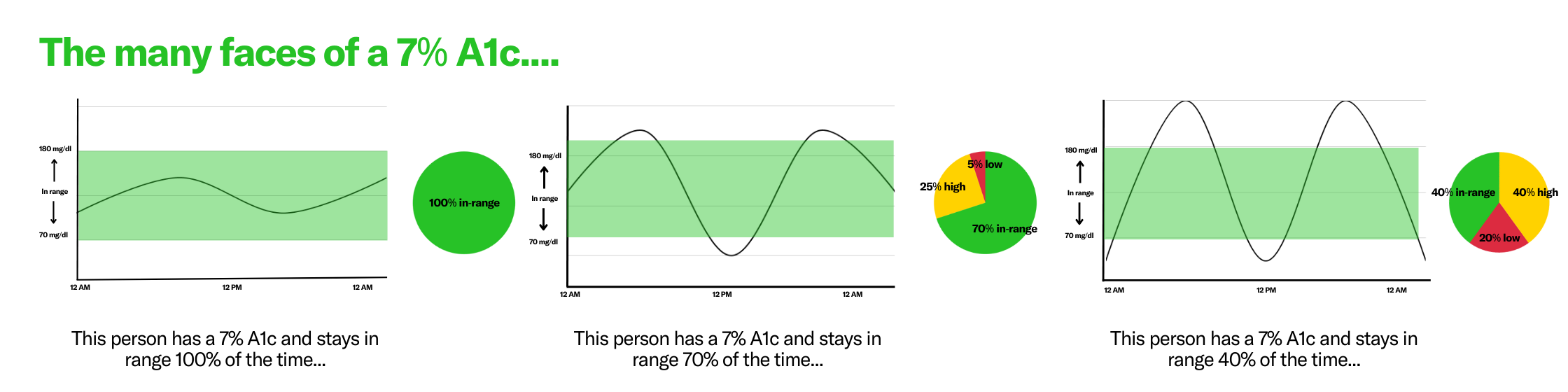

In 1993 (yes, over 30 years ago), the Diabetes Control and Complication Trial (DCCT) and United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS, 1997) established an association between HbA1c (A1C) and microvascular complications. Since then, A1C has become a gold standard metric in the management of diabetes. However, many recent publications have realized the shortcomings of A1C in optimizing diabetes management in people with diabetes.

The major question: Is time in range as good as A1C in predicting diabetes-related complications?

To investigate this, Dr. Roy Beck estimated time in range from fingerstick data collected during the DCCT trial. The results showed that time in range could potentially be an accurate predictor of microvascular complications.

More recently, Dr. Viral Shah designed a retrospective study to examine the relationship between CGM metrics and retinopathy. He included participants with incident diabetes-related retinopathy (those who were diagnosed with retinopathy during the study period but never had it before) and participants without diabetes-related retinopathy and collected their CGM data over 7 years before their retinopathy diagnosis. He found that time in range could be a significant predictor of incident diabetes-related retinopathy—after adjusting for age, diabetes duration, and CGM type, every 5% decrease in time in range was associated with a 22% increase in odds of incident diabetes-related retinopathy.

In addition, the study showed that time in range, time spent between 70-140 mg/dL, HbA1c, time above range (>180 mg/dL), and mean glucose were all highly correlated, indicating they provide very similar information on the risk of diabetes-related retinopathy.

In a very recent study, Dr. Kovatchev and his group simulated CGM data for DCCT participants using fingerstick data collected during the original study to evaluate the association between time in range and microvascular complications. Unsurprisingly, they found a similar association between time in range and diabetes-related microvascular complications among DCCT participants.

Overall, we know that we can help reduce the risk of diabetes-related complications by utilizing time in range in practice: when time in range is increased, complication risk decreases. Time in range shows us the entire picture and allows you to take action to help protect the long-term health of those in your care.

Remember that while increasing time in range has incredible benefits, individualizing care and ensuring that realistic and attainable goals are being made with those in your care is vital. Time in range can sometimes feel like a grade for people with diabetes, however when you can focus on health behaviors, a person’s specific wants, needs and health goals, and the psychosocial impacts of diabetes, instead of just the numbers, it can help reduce those feelings of judgment and help people with diabetes live their best lives.

References:

- Beck R. Validation of Time in Range as an outcome measures for diabetes clinical trials. Diabetes Care 2019; 42:400–405

- Shah VN et al. Time in range is associated with incident diabetic retinopathy in adults with Type 1 diabetes: A longitudinal study. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics 2024:26 (4): 246-251

- Kovatchev BP. The Virtual DCCT: Adding Continuous Glucose Monitoring to a Landmark Clinical Trial for Prediction of Microvascular Complications. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics 2025, Online First.